By Diroug Markarian Garabedian

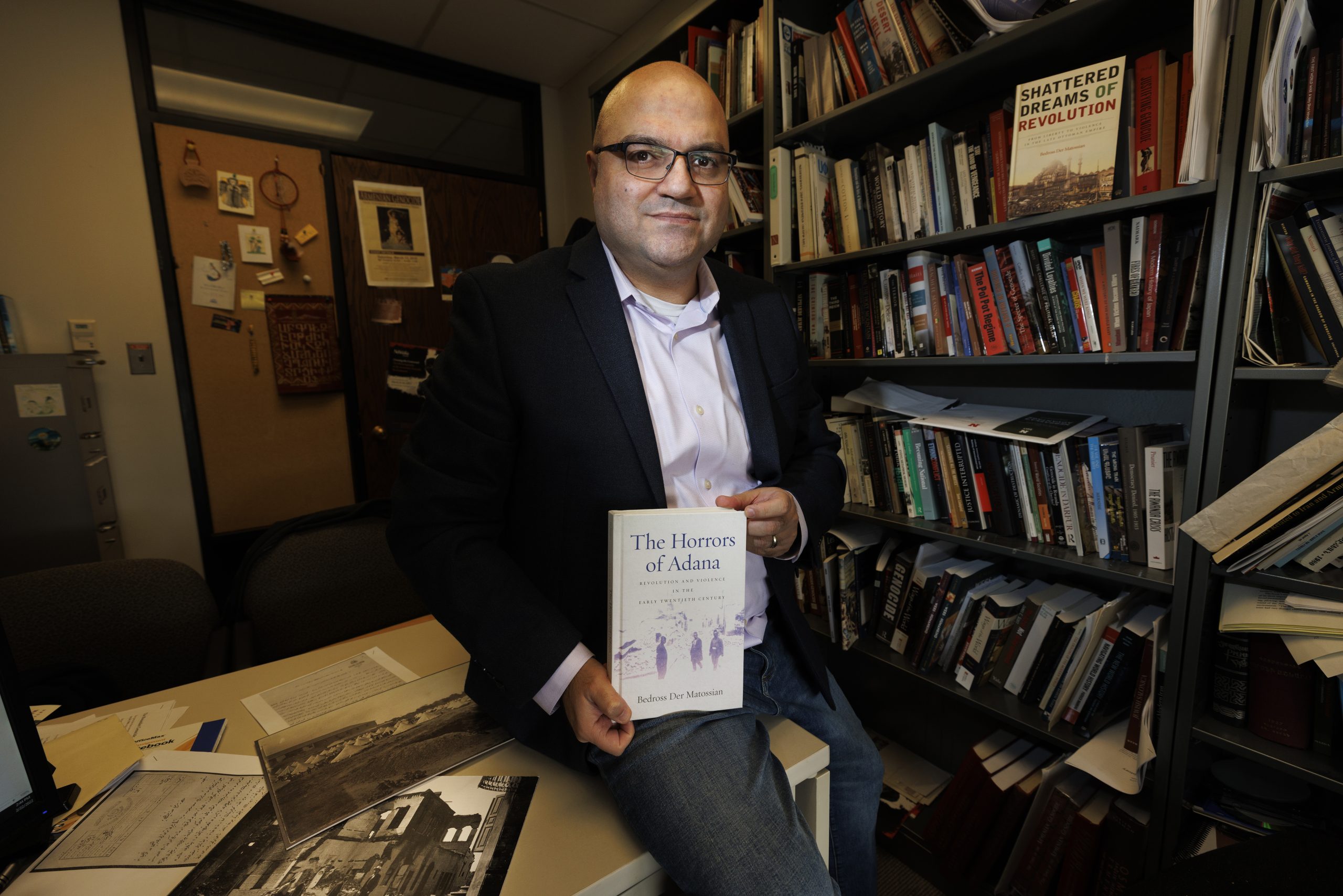

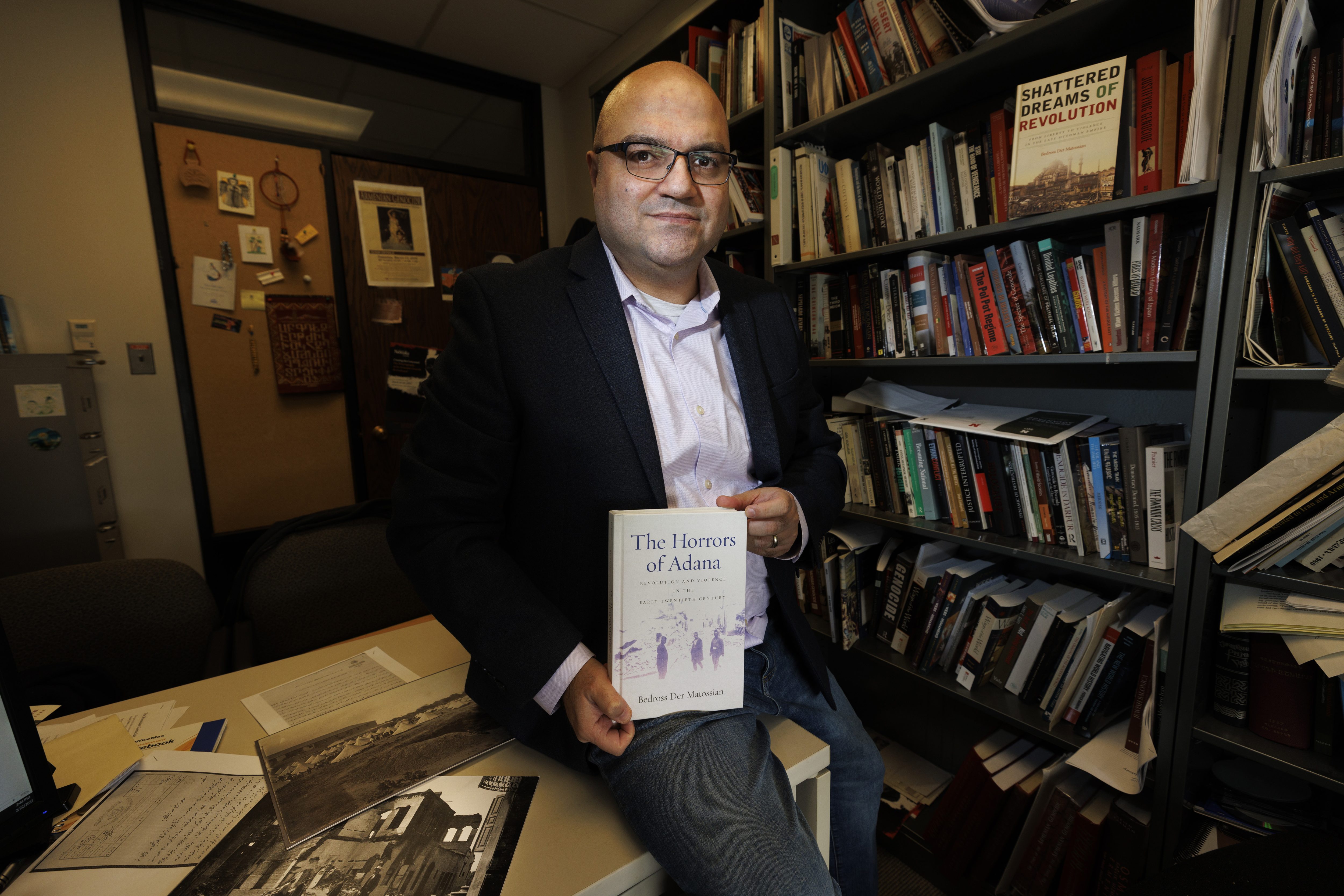

A thought-provoking presentation-lecture entitled “Revolution and violence in the early 20th century” based on his latest book, The Horrors of Adana (Stanford University Press, 2022) was delivered by the volume’s author, Professor Bedross Der Matossian, at the AGBU headquarters in Toronto on June 24.

The event opened with a beautiful rendition of Arno Babajanian’s musical piece “Elekia” by pianist Hrag Karamardian, after which the evening’s mistress of ceremonies, Anna Maria Mubayyed, introduced Professor Der Matossian.

Der Matossian is the vice-chair of the Department of History at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln (UNL), an associate professor of modern Middle Eastern history, and also serves as president of the Society of Armenian Studies (SAS).

He was born and raised in Jerusalem, where he graduated from the Hebrew University. He received his doctorate in Middle Eastern History from Columbia University’s Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies. From 2008-2010, he was a lecturer in Middle Eastern History at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). In the spring of 2014, he was a visiting lecturer at the University of Chicago. He is the author, editor, and co-editor of multiple books, including the award-winning Shattered Dreams of Revolution. From Liberty to Violence in the Late Ottoman Empire (Stanford University Press, 2014).

Below is Torontohye’s exclusive interview with Professor Bedross Der Matossian.

Diroug Markarian Garabedian: A lot of information that has been forgotten due to Turkish revisionism is included in your valuable book. What problems do you think these revelations will cause for the Turkish government?

Bedross Der Matossian: The most significant thing to remember is that the Turkish “deniers” do not use Armenian sources or archives. In general, these individuals rely only on the Ottoman archives. My book is based on sources existing in 12 languages: Arabic, Hebrew, Ottoman, Armenian, Turkish, Latin, German, Greek, and French, among others. As I mentioned in my lecture, I have used these sources to give voice not only to the victims but also to the perpetrators and bystanders who refused to help Armenians.

I await critical reactions from the gatekeepers of Turkish official history and individuals who will undoubtedly deny my scholarly findings. In the book, I emphasize that Armenians did not have a plan to revolt against the government. Based on the archives of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), I argue that the extensive purchase of weapons by the Armenians in the post-revolutionary period was aimed at self-defense and not for sinister aims of restoring the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia.

TMC: How did the European market react to the massacres, especially the countries that import cotton from Adana. Did they try to defend or support the Armenian victims in any way?

BDM. The European economy, especially the German one, in the sense of importing cotton, was affected in that period. In April, cotton production received a severe blow due to the massacres. The Europeans had somehow controlled the cotton production market, and the massacres affected the German establishments with the cotton factories. Still, the Europeans did not carry out any humanitarian intervention. Instead, they provided some humanitarian assistance, helped the Armenian refugees, treated the wounded, and provided food to the destitute. By contrast, in the 19th century, humanitarian intervention meant military intervention by European powers to prevent massacres or to provide assistance, as was the case in the 19th century in Lebanon, Crete, and Greece.

Some of the reasons for the lack of humanitarian intervention during the Adana massacres were the following: European powers had scores to settle among themselves and did not want to risk altering the status quo or losing the balance of power on the European stage. Humanitarian intervention could have occurred when all European powers realized that none of the invested nations would benefit from their intervention. Russia was on the side of the Armenians, while England, France, and Germany were on the other side. The latter group had conflicting policies toward the Armenians.

TMC: – Inheritor governments of successive regimes in Turkey continue denying the facts. How much has the denial of what happened during the Adana massacres or the Armenian Genocide intensified since the publication of this volume?

BDM: There is a critical question before us today. Is the denialist approach to the massacres in Adana the same denialist approach that the Turkish government had in 1909? Does this government try to “prove” that what happened in Adana was a rebellion against the Ottoman state and whose goal was to re-establish the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia? This purported plan would also have included the invasion of the Europeans on Adana through whose support that Kingdom was going to be established. Yes, this is the same thesis of 1909 and the 1950s, written by Esat Uras (a perpetrator of the Armenian Genocide and prominent official of the Committee of Union and Progress). His book, The Armenians in History and the Armenian Question, is a canonical text of Turkish nationalist/denialist historiography. In this book, he rehashed the same arguments made in the Idital newspaper about the two massacres at the time they occurred. Let me say that to this day, Uras’ book continues to inspire Armenian Genocide deniers.

TMC: Those who planned and carried out the massacres try to cover up the reality and continue their self-deception by denying the 1915 genocide. To what extent will they succeed in spreading their propaganda when the archives are full of materials showing the massacres and genocide took place?

BDM: The word “genocide” is accepted in the academic world [in the case of the Armenians], but as we know, the Turkish state spends millions of dollars every year and makes every effort to deny the Armenian Genocide through its embassies, consulates, student organizations at American universities, and cultural associations. It is a well-organized campaign. And what happened in Adana was an organized massacre. The violence soon spread throughout the province and reached the east, to the province of Aleppo. The Ottoman government sent investigative commissions and appointed Courts Martial to try the criminals. Still, these courts did not hold the main perpetrators of the massacres responsible, leading to a miscarriage of justice. Massacres are such a complex subject that we cannot analyze them solely from a historical point of view. We must look at them from a theoretical perspective and consider the perpetrators’ psychology, social and economic incentives, and various conditions surrounding the massacres. Turkey, of course, has always denied massacres and the Genocide.

TMC: What is the contribution of this book to the academic world?

BDM: I hope the book will enlighten the academic world and the general public about these massacres. The aim is to present the Adana massacres of 1909 as a crime not only against Armenians but all of humanity. The book also analyzes the events globally because similar massacres occurred in the 20th century in different societies, cultures, and religions. Indeed, this approach will better understand the phenomenon on a global scale. The structures of the violence that took place during these various massacres are the same; they include the collaboration of the government, soldiers, police, and other forces in different regions. Investigation commissions were formed and courts martial were established to try the culprits in other cases as well. However, most of the massacres that took place throughout the 20th century were not met with justice. There is an additional value in this work in that it contributes to a new field of study called massacre studies.

TMC: What are some of your future plans? Are there any new works or volumes on the horizon?

BDM: Next year, my edited volume, Denial of Genocides in the 21st century, will be published by Nebraska University Press. This book presents a serious approach not only to the denial of the Armenian Genocide but also to the denial of the Holocaust and the Rwanda, Cambodia, Bosnia, and Guatemala genocides, among others. The authors in this book include social scientists and historians who discuss the latest methods of denialism, such as the use of social networks, academic venues, and legal measures.

An Armenian version of this interview was published in Torontohye on July 8. Read it here.