A century ago, a group of Armenian boys arrived in Canada in what many historians have suggested constituted the nation’s first large-scale humanitarian effort—“Canada’s Noble Experiment,” which resulted from the efforts and actions of concerned citizens and nongovernmental organizations.

As the Armenian community of Canada gears up to celebrate the centennial of the arrival of the first group of Armenian survivor children to Canada, we sat down with the Sara Corning Centre for Genocide Education’s Director of Research, Daniel Ohanian, to learn more.

Torontohye: Why are we marking the centenary of the Georgetown Boys and Girls’ story this year?

Daniel Ohanian: The short version of the Georgetown story is that, between 1923 and 1930, the Armenian Relief Association and the United Church received federal government permission to bring over 150 boys, girls, and women displaced by the Armenian Genocide—most of them orphans—to Canada.

2023 marks a hundred years since the first group of boys arrived.

But the story has a longer background, and it was a serious challenge for the association to pull it off.

Canadians started learning about Armenians in the late 1800s in a very gradual way. Between 1860 and 1915, around 50 Canadians went to the Ottoman Empire to work with the Armenians as missionaries, setting up schools and medical clinics and spreading Protestant-Evangelical Christianity. During anti-Armenian massacres in the 1890s and 1909, these missionaries sent news about what was happening to churches and newspapers in Canada. That’s how Canadians started to learn about what sorts of people Armenians were and where they lived. A stereotype was created that was very useful for several fundraising campaigns run in those days: Armenians were a persecuted, suffering, pitiable Christian people in the East who needed help. This stereotype was used again during the genocide and after it, to great effect. Between 1915 and 1930, non-Armenian Canadians donated $1 million (roughly $17 million in today’s money) to help Armenians abroad.

Georgetown is part of this story about missionaries and fundraising, but it’s also different from it. One of the essential differences is that the suffering-Armenian stereotype was both a blessing and a curse for the Georgetown project.

Torontohye: How so?

Ohanian: Armenians were being killed and displaced not just in 1915 but for about 15 years after that too. The genocide took place in phases, and wars and economic crises prevented roughly half a million survivors from putting down roots right away. One of these wars (the Turkish War of Independence led by Mustafa Kemal, later named Atatürk) threatened orphanages all over what is today Turkey. The question of what to do about the orphans there led a group of men in Toronto to try something new.

In 1922, in response to panicked telegrams from Constantinople, the Armenian Relief Association negotiated an agreement with the federal government to let in groups of orphans as a humanitarian undertaking. The proposal was to do something that would fit both the government’s interests (increase the number of farmers in the country) and the interests of compassionate citizens and refugees’ (save lives).

One of the challenges the association faced was convincing officials that this was a good idea. This is where the suffering-Armenian stereotype was a curse. What was then called the Department of Immigration and Colonization had a track record of being culturally intolerant. It had already put up legal barriers to keep people from Asia—including Armenians, Indians, Chinese, and others)—as well as the impoverished and the stateless, from moving to Canada. In their internal discussions, immigration officials described Armenians as inherently or culturally inferior to Britishers and too carefree about cheating and lying. They also pointed out—and rightly so—that there weren’t many Armenian farmers in the country. It was clear to them that these run-down, non-British non-farmers shouldn’t be allowed in.

It was a spirit of tenacity and compromise that carried the day. As far as we can tell, the relief association was allowed to set up its farm-orphanage in Georgetown because Prime Minister Mackenzie King, who’d previously rejected the idea, changed his mind after hearing from close personal friends, political allies, and, in varying ways, tens of thousands of citizens. At the same time, the association had to settle for far less than it had initially wanted. It received an immigration quota of 100—only two percent of the 5,000 for which it had agitated.

The Georgetown Armenian Boys’ Farm Home was set up as a 200-acre training orphanage modelled after what were called industrial schools. It received its first group of student-orphans, aged roughly 10-12, on July 1, 1923—what was then called Dominion Day, now known as Canada Day. The next seven years were full of growth, challenges, and adaptation. New quotas were received for more boys and girls and women too. Donors, reporters, and neighbours came to see the work being done at the farm home firsthand. Interviews were given, concerts were organized, and money was collected. The boys were sent out to work on farms, and the girls and women were to work as maids. After a few years, the project was taken over by the United Church of Canada before being wrapped up on the eve of the Great Depression in 1930. To my knowledge, the last Georgetown Boy, Yervant George Makinisian, died in 2004, and the last Georgetown Girls, Aznive Lorna Campbell-Merson and Armenouhi Armine Kavookjian-Turmanian, died in 2011.

Torontohye: What has been planned to mark this centennial?

Ohanian: The organizing committee is planning at least two events: The main event will be held in June at Cedarvale Community Centre in Georgetown in partnership with the Town of Halton Hills. We’ll publicize details in the spring.

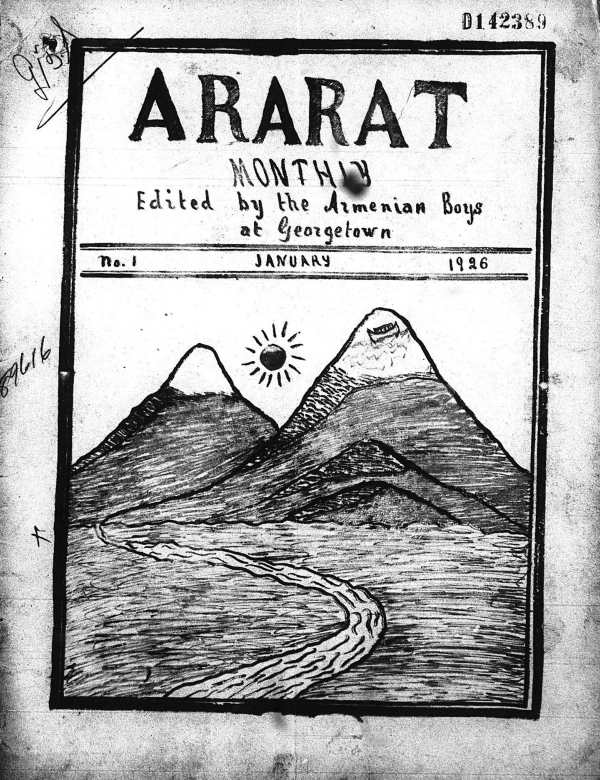

The second event is a book launch. Something the Corning Centre is working on this year is to republish Ararat Monthly / Արարատ ամսաթերթ, the official newsletter of the Georgetown Boys. Ararat was the brainchild of the Boys’ Armenian teacher and older-brother figure, Aris Alexanian. Newsletters like this were used by Armenian and non-Armenian orphanages to share the news with past and prospective donors and to give children something creative to work on. Aris published about 45 issues over four years, 15 in English and the rest in Armenian. It was an impressive undertaking. In the early years, the Boys would write articles and stories and draw pictures; their contributions would be typed up, and the newsletter would be sent to readers in Ontario, the U.S., France, and Soviet Armenia.

Torontohye: How does one go about collecting issues of a newsletter published almost a hundred years ago? Have they been compiled before?

Ohanian: We’ve been working to collect originals and copies of Ararat since 2012, but they’re tough to find. We have almost a complete set now; we’ve found them scattered among families, libraries, and archives in Toronto, Paris, and Yerevan. We’re still missing a few issues, though. If any readers have copies, I ask them to write to dohanian@corningcentre.org to donate the originals or share photos—whichever they prefer.

We’re also happy to say that we are partnering with Torontohye to publish an issue dedicated to Georgetown Boys and Girls later this year.

Torontohye: In 2010, thanks to the efforts of the Armenian National Committee of Toronto (ANCT), Cedarvale Park was designated an Associative Cultural Landscape. A year later, a provincial plaque was installed to commemorate the Armenian Boys’ Farm Home. There have recently been some whispers in the community about the fate of the building that currently houses the Cedarvale Community Centre.

Ohanian: Actually, the future of the community centre is, in fact, unclear.

Until a few years ago, most believed the building was the original farm home. In 2020 or 2021, the town was conducting an architectural assessment and discovered that it was not the original farmhouse. They contacted us, and the Corning Centre investigated. Based on almost 100 archival photos and maps, we were able to see that the architects were right.

The future of the building is unclear, and the building will likely lose its protected status and be demolished by the town since it’s in poor shape. The town will be well within its right to do that. But given the symbolic importance of the site in general, as well as the habit Armenians in Ontario have made of visiting the site, we’re talking with the town about ways to continue marking the Georgetown story there.