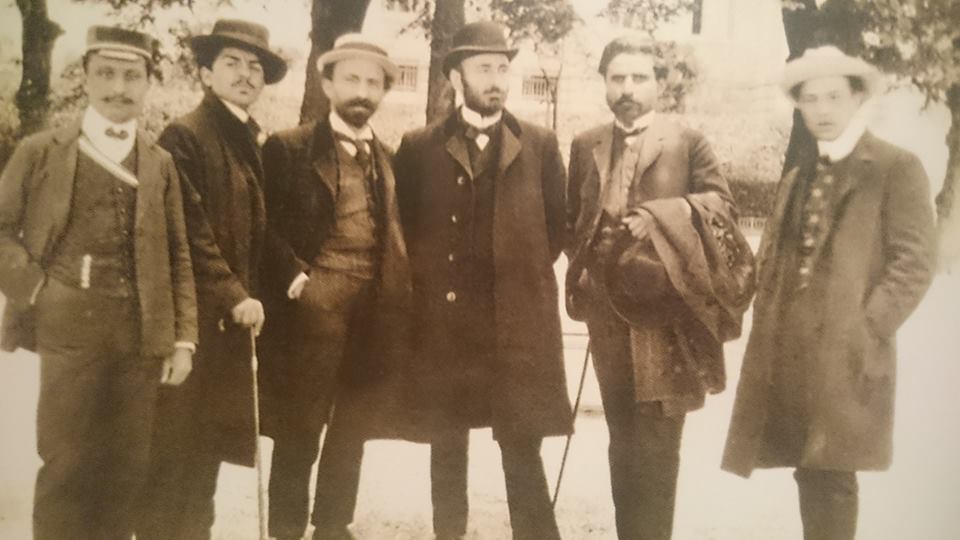

Komitas, Ruben Sevag, Chobanian, Gasbar Ipekian 1907, Lausanne.

By: Araxie Altounian

2019 marks the 150th anniversary of Father Komitas, the priest-musician known as the “Father” of Armenian classical music. To most Armenians he is best known as the savior of Armenian musical heritage, having collected thousands of traditional songs, arranging some of them for voice and piano, or for choir, thus bringing them to the concert stage. Over the past century, these songs have found a special place in the hearts of Armenians scattered around the world, creating a spiritual connection to a lifestyle and a culture from which they were brutally removed, while Komitas himself became a symbol of the martyr of the Armenian people during the 1915 Genocide.

Moreover, while Western Armenians were struggling to build new communities in foreign countries, and while Eastern Armenia was shut behind the Soviet “Iron Curtain”, Komitas, who had once been one of the best known Armenians in Europe, fell into oblivion on the international stage, his music limited to Armenian and some Russian consumption.

If the 20th century was cruel to Armenians and their culture, the 21st century brings new opportunities, casting Komitas in a brighter light. The Komitas Museum-Institute in Yerevan and its group of dedicated scholars work tirelessly along with foreign experts to place Komitas on the international scene once again. Extensive research, annual conferences, the latest of which took place at the Sorbonne university in Paris in the fall of 2018, the publication of all the newly presented papers in annual yearbooks, and posting these on the Museum-Institute’s website, make Komitas much more accessible to the interested public worldwide.

Rather than refute past concepts which remain factual and true, new research highlights aspects of Komitas’ person and art that had been overlooked in the past. For example, the image of the symbol of Armenian martyrdom overshadowed the man’s energetic, even humorous character. Komitas made great plans and pursued them with fervour and resolve. Not surprisingly, his intensity, combined with his talent and drive, made Komitas a highly charismatic person. At his funeral, German musicologist Curt Sachs stated in his eulogy, “Who could resist the tone of his voice and the glow of his eyes?”

Komitas lived at a time when Europe was engulfed in nationalistic movements that eventually brought down empires and replaced them with new republics. European musicians that he admired became symbols of nationalist schools, amongst them Richard Wagner in Germany, and Giuseppe Verdi in Italy (known as the Maestro of the Italian Revolution). His three years of study in Berlin had a profound influence on Komitas’ thinking. According to German musicologist Regina Randhofer, “Berlin was rather a catalyst for Komitas to exploit Armenian music for the national cause. For in Germany, in the XIX century pivotal discourses and strategies emerged, aiming at cultural nation building, demonstration of national unity and construction of identity. Thus, Germany offered a high potential of identification to the stateless Armenian community in the Ottoman and Russian Empire[s] at the time of ‘national awakening’”.

Komitas was in close contact with the intelligentsia of the Armenian Renaissance. Deeply concerned with the fate of his people at this critical historic time, he envisioned culture as the most powerful weapon to convince Europe that Armenians are not “merely a people begging for mercy”, but a civilized nation capable of contributing to human progress. His musical activities were strategically chosen to prove that point, and to place the Armenian people among the rank of civilized nations. They included: searching for the authentic Armenian traditional music and extracting foreign influence from it, a meticulous quest for a unique harmonic language that would preserve that authenticity, concerts and lectures in Europe, and academic papers that were published there, as well as in the Armenian media in Constantinople.

His determination “to excavate the sounds of our Armenian folk music from our historical ruins” aimed to prove to the world that the Armenian people possessed its own unique music and culture; and therefore, it was a nation that had its unique identity, hence the right to be recognized as an independent nation. Thanks to his extraordinary talent, Komitas successfully captured the hearts of his audience with his songs, and their minds with his lectures, thus making foreign experts acknowledge the existence of a unique and beautiful Armenian music, and, in the words of German musicologist Max Seiffert, that of a “high civilization” whose presence they had so far ignored.

Komitas’ search for a national musical identity went beyond the collection of traditional songs, their analysis and classification. While arranging the traditional monodic material, he incessantly looked for a harmonization that would preserve its original character. In a letter to Marguerite Babayan dated 1907, Komitas explains his approach: “Armenian melodies as well as their expression require the simplest possible harmonization, which is very difficult to do. Moreover, we, Armenians, must first create a national idiom, and only then confidently move forward. So far, I have been influenced by others and only now am I starting to harmonize Armenian melodies with an appropriate style. When I feel perfectly immersed in the sounds of Armenian music, I write, and create something that’s suitable to the spirit of our music. But there are times when my imagination unwillingly wanders to a sphere that’s not Armenian. Nevertheless, I shall reach my goal, even if it costs me my life”. Richard Schmidt, his teacher in Germany, once had said “Komitas is an Eastern fanatic who is willing to spill blood for each note”.

Paradoxically, the desire to preserve a millennial musical style would be the impetus for a modernist compositional language. Komitas the progressive composer has often been overshadowed by the saviour of Armenian traditional music, but recent research has taken a more balanced approach. The composer’s experimentation with innovative harmonies and rhythm dates back to his years in Etchmiadzin, while setting traditional songs for choir. According to musicologist Tatevik Shakhkulyan, those harmonies and rhythms have so far not been found in the works of other contemporary composers, thus excluding foreign influence (Tatevik Shakhkulyan, Komitas and the XX Century Western Music, in Komitas Museum-Institute 2016 Yearbook).

Composer Tigran Mansurian brings to our attention the innovative use of the piano in Komitas’ suite of Armenian Dances: rather than adapt Armenian melodies to the rich pianistic style that was common at the turn of the century, it is the piano, an essentially western instrument that is made to imitate the sounds of Armenian traditional instruments such as the tar, tambourine and dhol among others, a novelty at the time. In a televised interview, Tatevik Shakhkulyan explains that while Armenians recognize their traditional tunes in Komitas’ work, the non-Armenian listener simply perceives it as modern music.

It is interesting to note that in spite of his exposure to Russian music (during the Etchmiadzin years), German music (during the 3 years of study in Berlin), and French music (during the numerous trips to Paris where he studied the works of contemporary avant-garde composers), Komitas’ work has its own distinctive sound, without betraying foreign influence – and that’s where lies the greatness of Komitas the composer.

While the World War I and the Armenian genocide put an abrupt end to the stellar ascent of this talented and admired musician, his work continued to arouse interest among Russian musicians since the Soviet period. More recently, classical musicians specializing in Early Music are discovering Armenian medieval and folk music in general, and Komitas in particular and including them in their repertoire (see: Alyssa Mathias, “Programming Armenian Folk Music in United States and Western European Early Music Ensembles”, in Komitas Museum-Institute 2016 Yearbook).

Building on this momentum would allow Armenians to once again bring Komitas to the attention of foreign audiences in creative ways, through the medium of “Word Music”, “Early Music”, or even “Avant-garde Music” in addition to the more conventional “Classical Music”. As western audiences grow more diverse and look for novel concert experiences, a well planned and innovative program including Komitas may be just what they wish to explore. And some well-known Toronto based Armenian musicians will be doing just that in the months and year to come. More about them later…