By Dr. Araxie Altounian

Musical minds is a conversation series with established, talented Armenian musicians with a Canadian connection who contribute to Armenian musical culture in innovative ways and build bridges between the Armenian diasporic community and its host societies. AGBU Toronto has graciously provided its Zoom platform for live broadcast on Facebook, and its recording on Facebook and Instagram, while Torontohye has been kind enough to publish them.

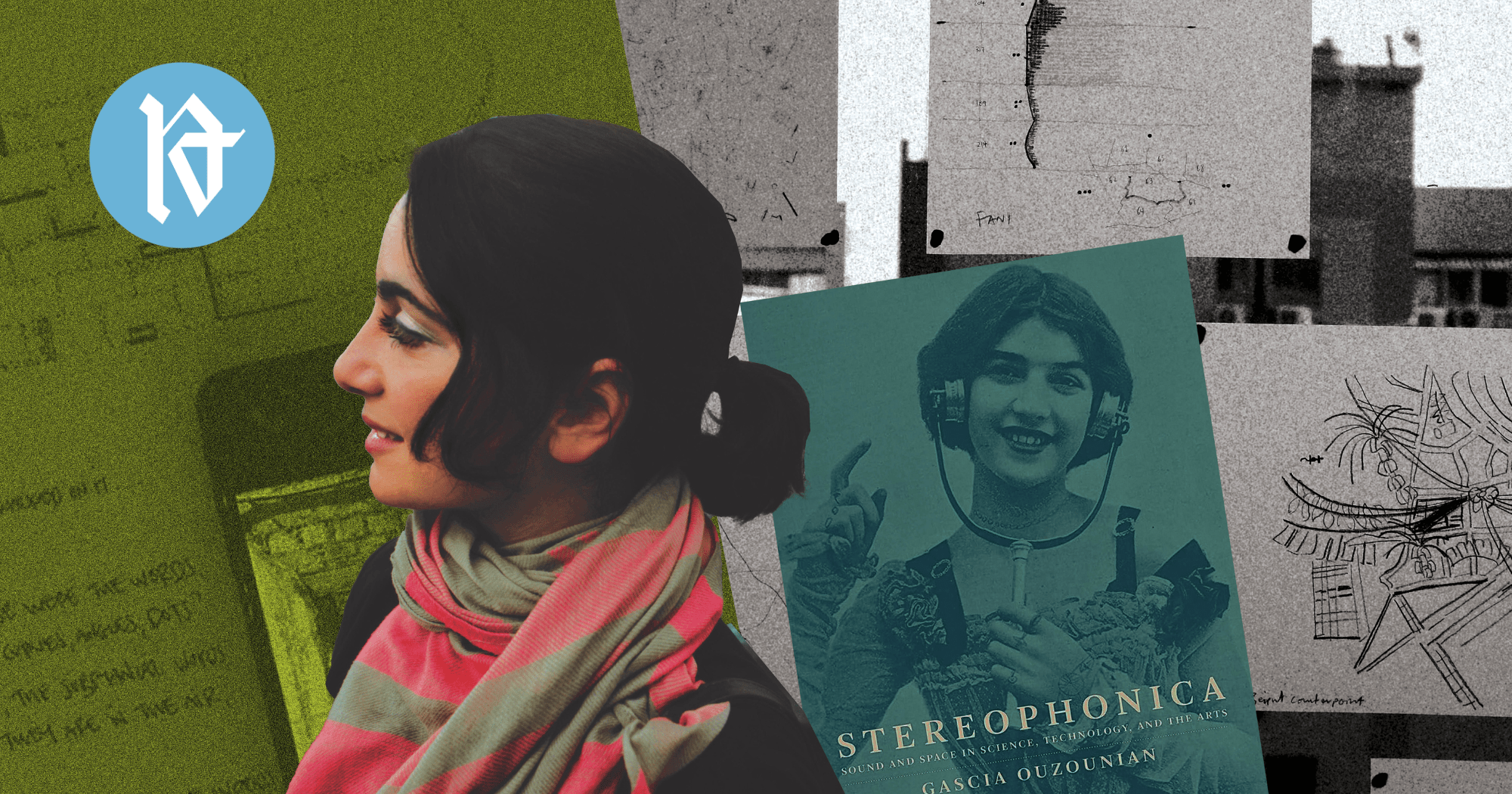

The following is based on my conversation with my third guest, Musicologist/Sonic Theorist Dr. Gascia Ouzounian.

Dr. Ouzounian is an Associate Professor of Music at the University of Oxford and a Fellow and Tutor in Music at Lady Margaret Hall. She studies sound in relation to space, urbanism, and violence. She is the author of Stereophonica: Sound and Space in Science, Technology, and the Arts (MIT Press 2021) and has contributed articles to leading journals of music, visual art, and architecture. In 2013 Ouzounian co-founded the research group Recomposing the City, which brings together sound artists, architects, and urban planners in developing interdisciplinary approaches to urban sound studies and urban sonic practices. Recent projects include Scoring the City (2020-ongoing), which explores experimental notations for urban design, and Acoustic Cities: London and Beirut (2019), for which ten artists created works that responded to the sonic, social, and spatial conditions of London and Beirut. At Oxford, she currently directs a 5-year project funded by the European Research Council on sonic urbanism, Sonorous Cities (2020-2025).

Araxie Altounian: Gascia, you come from a family of three very talented and polished musicians. Your older sister, Maral, is a fine pianist who eventually chose a medical career, you are a violinist turned sonic theorist, and your younger sister, Karen, is leading a successful career as a cellist. Could you tell us what it was like growing up in the Ouzounian family as a budding musician?

Dr. Gascia Ouzounian: It was a wonderful family to grow up in, a very musical family. My parents were very interested in our musical education since we were young. We were encouraged to pursue music when we were studying at the Hye Getron, then at the Royal Conservatory of Toronto, where we took lessons and had incredible teachers. That led to more serious studies at the university. It was a very vibrant home, and it’s something that I love seeing passed down to my sister’s children, who are also extremely musical. It’s an incredible opportunity to be raised in a home like that.

Altounian: Can you tell us about your journey from violinist to sonic theorist?

Ouzounian: I’m still doing some performances and collaborating with composers and other artists, like visual artists, people working in multimedia. I had a wonderful undergraduate program when studying at McGill University, where I could study violin performance and computer music/music technologies simultaneously. It was important to be exposed to that world: computer programming, acoustics, and the science of sound. From there, I went to the University of California in San Diego for my Ph.D., where there was a unique program called Critical Studies and Experimental Practices in Music. We were focused on the philosophy of music and sound, cultural studies in music, and a wide range of contemporary music practices, and experimental music, both within the Western art tradition and beyond. When I was there, I started looking into the history of sound installation art: that’s what my Ph.D. was on. It was concerned with sound sculpture and extended forms of sound in gallery spaces. So, things went somewhat outside the musical traditions, inspiring me to write about sound artists. I realized I could do this by interviewing artists, visiting museums and galleries, and looking at their archives. At the time, there wasn’t much historical or academic work done in that realm, so it was an exciting moment to be doing that kind of work. That’s how I made the shift.

A.A.: Your book Stereophonica looks at the different aspects of sound study: sound and technology, sound and war, sound and music, sound and urban environment, the effect of sound on our well-being… Could you briefly explain to our viewers what sound science is and how it affects our lives?

Ouzounian: In my first book, Stereophonica: Sound and Space in Science, Technology and the Arts I challenge the idea that we can only look at sound and acoustics in the realm of science. There’s also a fascinating cultural history of acoustics, ways in which science, technology, and the arts are deeply intermingled. The book looks at ideas of acoustic space or auditory space, the space of sound and hearing, and how these ideas evolved from the 1850s to the present day. My book looks into particular moments in time and how ideas of sound and space changed. For example, I looked at the rise of the binaural listener; the person listening with both ears in a spatially oriented sense is something we take for granted today, but that was not always the case. Many psychologists thought that hearing was not spatial and that sound could not convey spatial attributes, but that changed over time. One early example is Alexander Graham Bell, one of the inventors of the telephone, holding two receivers to his ears, trying to sense how far away someone is when you’re listening or where they are. Of course, this was a new kind of technologically mediated form of audition – no one had listened through a telephone before 1880. Bell claims that “there seems to be a one-sidedness about sound received through a single ear, as there is about objects perceived by one eye when both ears are employed simultaneously sounds assume a ‘solidity’ which was not perceptible so long as one ear was employed”. This is where the idea of ‘solid’ comes from. He coins the term ‘stereophonic’, ‘stereos’ being the Greek word for ‘solid’. I tried to unpack the history of how scientists think about how we hear in relation to space.

The book covers a lot of ground, but I will mention another chapter that was very interesting to research. It was about acoustic defense, how people tried to defend their territories through listening during the First World War. This became important with aerial warfare, especially around cities. They were developing these very experimental technologies during the war for sensing where something is through the sounds it makes. The idea of spatial listening became very important. There was a lot of research done during the First World War because of this need.

The book also talks about the links to musical practices. Scientific ideas are shaping compositional practices, being able to send sound through different channels that today we call multichannel sound. But there is a real link between military science, acoustic science, composers, and practitioners. Some of them were working in the same research centers and collaborating.

A.A.: “Sonorous Cities” is the name of a 5-year long project on the theme of sonic urbanism and of which you are the director. It was made possible by a generous grant from the European Research Council. What is this project about, and what makes it important?

Ouzounian: Before Oxford, I was working at the Queen’s University in Belfast and noticed that a lot of sound artists were doing things in public spaces, things that were changing how the space is experienced, navigated, or understood, sometimes doing politically interesting things as well, because Belfast is a historically segregated city, divided along religious and political sectarian lines. The main designers of space are architects and urban planners. Still, it seemed to me that there was not much communication between those two groups: people doing sound at a very high level and people doing work with designing spaces. Ten years ago, along with architect and architectural historian Sarah Lappin, we started a group in Belfast called “Recomposing the City” that brought the two groups together, hosting seminars and interdisciplinary teaching between faculties, looking at sound and architecture, not only around acoustics and sound control, the way sound has historically been treated in architecture to mitigate noise and control sonic reflections in the space, but a more critical, creative, sound-art type of work and being in dialogue with architecture. From that, we developed this more recent project, “Sonorous Cities”, towards a sonic urbanism. The research team is based at the University of Oxford, though there are quite a few people associated with us on this project. We’re doing cross-disciplinary work between sound and architecture; some of it is critically oriented. We’re looking at urban soundscapes and sonic environments, not only in relation to what sounds you can hear but why they are there. Why are certain sonic cultures supported and become privileged? There are a lot of sound-related policies in a city. Some peoples’ sonic cultures are more policed than others; some are more diminished, whereas some people can participate in shaping the sounds of the city. So, we’re interested in the social aspect and do it through ethnographic research.

A.A.: Beirut is one of the cities included in your research [“Acoustic Cities: London and Beirut,” optophono.com]. You present several Lebanese artists and their projects about sonic urbanism, tackling various themes, such as preventing the partial privatization of one of the most popular public spaces in Beirut, excessive levels of urban noise, and memories of war. Could you briefly describe these projects?

Ouzounian: I went to Beirut several times and had workshops and modes of exchange with artists. Once, we did a week-long workshop called “Urban Sound and the Politics of Memory” to think about the sonic traces of Beirut’s complicated past and how you can hear those histories in the city today. Here’s an example of an inspiring project by Nathalie Harb, a sonographer, called the “Silent Room” (2017). She put a two-story temporary architecture in a parking lot in Beirut, in a low-income housing community surrounded by highways. Beirut is a city with excessive traffic and construction noise, where noise policy is not very developed. She was thinking of noise as a form of social injustice, saying the city’s wealthier residents can escape the noise, go to the villages or the upper floors, or they don’t have to work on the street. But the construction worker, for example, can’t escape that. She wanted to bring attention to that. The Silent Room is a free space that anyone can enter. It’s an acoustic sanctuary. I thought this was a fascinating intervention, thinking about how noise affects people differently and who have the ability to be protected from noise.

In another interesting project, “The Invisible Soundtrack”, sound designer Nadim Mishlawi, used hydrophones to record sound underwater in a very popular public space [Raouché]. After the war, many public spaces were privatized, and the design was outsourced to international “starchitects’.” He discovered a vibrant underwater soundscape. He tried to reveal what was being lost when such a space became inaccessible, and we don’t even know what it is.

One other work that I found interesting and pertinent to Beirut and many parts of the world is “Concrete Sampling” by Joe Namy and Ilaria Lupo. They spent several months with Syrian refugee construction workers, some of whom live in the construction sites. They used construction tools to play with that space and turn it into a sound piece. When they invited people to this “performance” they said it was an electrifying moment because the Syrian refugee population is invisible in some ways in Beirut even though it is very audible in the construction world. There was a very powerful moment of connection between the people who gathered to listen and the Syrian construction workers, all boys and men.

I was interested in looking at some of these practices and what they reveal about Beirut’s history. These artists are doing things that are worth paying attention to.

A.A.: Could you please explain what it means to “score a city”? You and your colleagues have scored several cities worldwide, including Beirut and Yerevan. You were in Yerevan with Canadian-Armenian pianist-composer Eve Egoyan. Can you give us an insight into your activities there?

Ouzounian: I developed the workshop “Scoring the City” with an urbanist colleague, John Bingham-Hall. We were interested in experimental musical notation, the graphic score that is almost like a visual art piece and quite present in Western art music tradition since the 1960s. We wondered if we could use this kind of score as a model for what architects and urban designers are doing in their kinds of drawings. Often, they work with two-dimensional forms like a blueprint or a plan and imagine their designs as a fixed form with only one outcome. Still, a score like this is an open and dynamic form you can interpret differently. There are chance procedures, improvisation, and elements that cannot be predicted. They invite performers to make decisions on how to interpret them.

We got together in six or seven different cities, always going to a particular site to think about it and its history, taking walks together, listening, and asking architects if they were able to imagine the future of that site and how they would score it, to do a design that would bring in elements of choice, improvisation, and informality. It’s a form of question, a proposition about how this would change their practice just as graphic score changes notational practice in music.

I went to Yerevan with Eve Egoyan at the invitation of the Crossroads Festival, presented by Quartertone, a contemporary music organization in Yerevan. We did the “Scoring Yerevan” workshop with students from the state conservatory and people in architecture and media studies. Eve did an interpretation of Earl Brown’s “December 1952,” an early graphic score. We talked about the choices one makes when interpreting these kinds of scores. We invited students to interpret some of these scores together. Then we did an outdoor exercise of notating the sounds we’re hearing in Yerevan and asked people to create scores based on those. Then the students performed some of those scores. It was an amazing opportunity to meet these outstanding musicians, students, and the amazing organizing team.

For me, scoring a city can have many meanings; but it’s thinking about how we communicate ideas through notational methods and how that can disrupt some of our practices, whether in music or architecture. It also has a dimension of listening to the city and thinking about the city as a sound world that we’re inhabiting and creating together.

Altounian: You wrote an impressive essay on earwitnessing the Armenian Genocide, titled “Our Voices Reached the Sky: Sonic Memories of the Armenian Genocide.” Could you please describe your work?

Ouzounian: This is a recent piece with open access. If you type the title in your web browser, you can find the article and download it for free. After I went to Yerevan for the first time in 2021, I came across an incredible collection of survivors’ testimonies. As I was reading them, I became interested in the sonic dimensions, what people actually heard. In genocide studies, we usually think about visual evidence such as photographs. The Genocide Museum-Institute in Yerevan, like many such places, is very visually oriented. Sound has generally been neglected in genocide studies. But when you think about what people heard, and their sonic memories (some people were thinking about these sounds over long periods, and some of the survivors were traumatized by the sounds that they heard), you can learn a lot about the Genocide by listening to those memories which carry a lot of historical and cultural significance and the psychology of what that trauma was like. Earwitness testimony – a mode of sonic remembrance – can reshape our understanding of the Genocide and its effects.

My source was an essential collection of survivors’ testimonies by Verjiné Svazlian, an Armenian ethnographer who, since her undergraduate years, went from village to village in Soviet Armenia when it was not possible to speak publicly about the Genocide to collect, record, and transcribe word for word 700 “memoir-testimonies” as well as 315 “song-testimonies.”I was thinking about her act of “counter listening,” meaning ‘listening against’ the official narrative of denial of the Turkish state. For over fifty years, she took a lot of risks listening to these testimonies. But it’s through her act of listening that people could tell their stories and sing those songs.

The paper goes through a lot of detail about what those testimonies show. Sound played a crucial role in producing the Armenian Genocide and its traumas. For me, it was essential to pay attention not only to how perpetrators used sound but to understand that even as they were left to die, victims had a voice. Those sonic memories have been transmitted through time through these collections of oral testimonies. Listening to sonic memories can enable voices that were concealed and denied by the state to sound and be heard, as reported by the survivors.