By: Shahen Araboghlian

My colleague put it perfectly on the fourth episode of the Meet the Revolution podcast. “When it comes to language, the Armenian language, there’s been some sort of online virtual renaissance, almost like a virtual զարթօնք (zartonk | renaissance) of Western Armenian, since this pandemic hit,” said Rupen Janbazian, the editor of h-pem.com. And he’s right, isn’t he? Unless you’ve been living under Patrick Star’s rock for the past three months, you’ve seen it, high and dry: the Western Armenian language, in action, en-ligne.

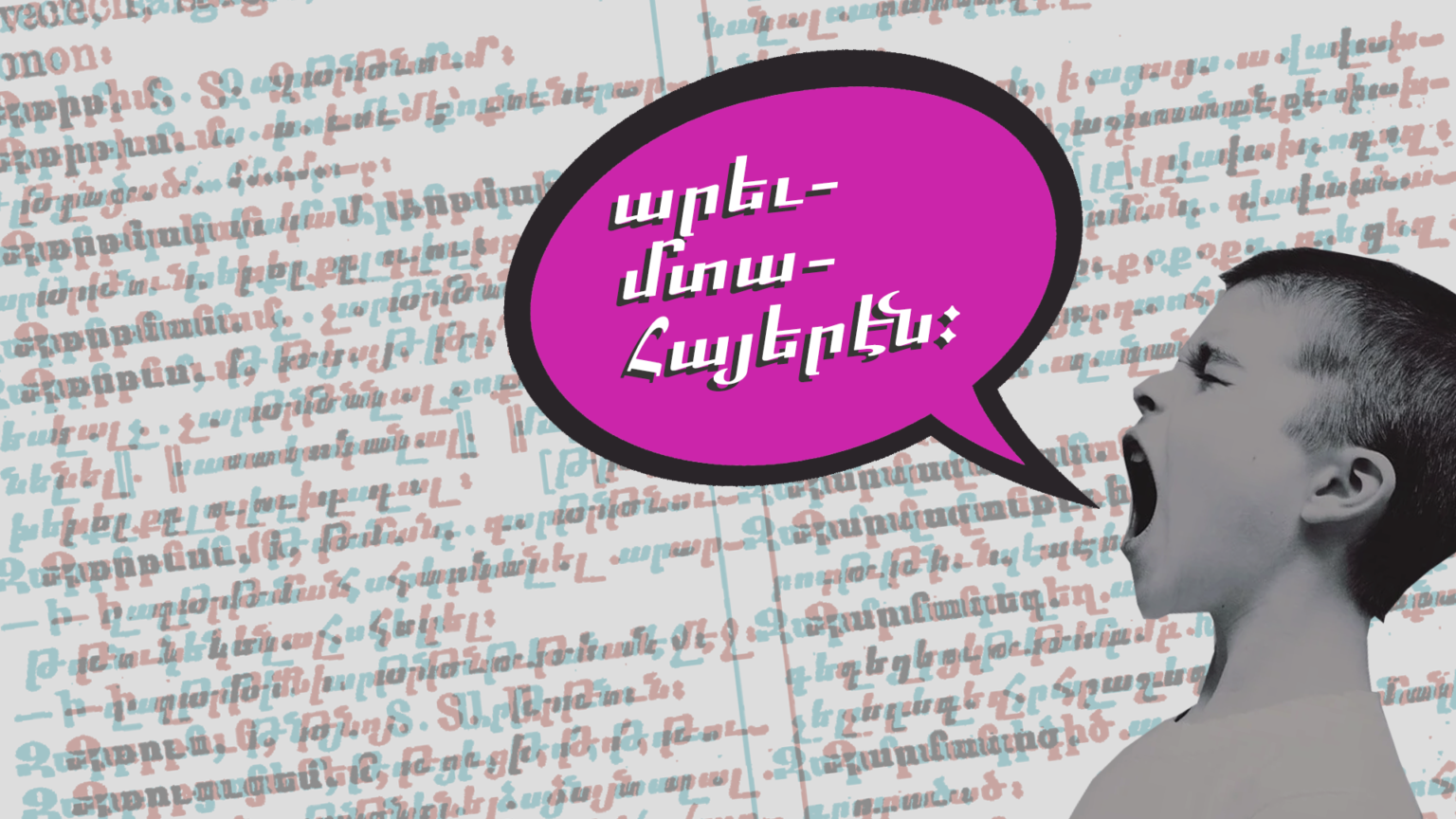

Back in February, the Armenian Communities Department of the Gulbenkian Foundation announced the “Creative Culture Program” for Lebanese youth to create in the Western Armenian language. It was Armstrong’s small step that launched a discussion on language revival using innovative methods. What came after was a global pandemic and the title of this piece: a boom in Western Armenian content that is creative, vocal, and witty in nature, incentivized by the starving need for daily familial and familiar conversations, online. Not in a textbook, not within the four walls of a classroom, not only about patriotism or nationalism, but about our present and every day; finally, like any other thriving language, alive.

In this piece, I will try and break down the multifaceted flow of virtual Western Armenian content, and wrap it up with a message to all those who think our language is dying, because it’s anything but.

Աղուոր Բաներ-esque (Aghvor Paner | “Nice Things”, inspired by poet Zahrad’s words, “when nice things happen, [consequently], nice things happen”) artsy pages have been sprouting left and right on my Instagram timeline lately, be it either old pages dusting off their creative selves or new ones taking flight into the great Western Armenian virtual unknown, from advocating for feminism, MayDay, and #BlackLivesMatter to making crafty alternatives of dialogue slang and calls to self-isolate.

Western Armenian podcasts are now a thing, mostly thanks to our better-than-ever culturally-thriving Armenian community of Istanbul. Heard of Ասպանդակ\Asbantag? What about «անուն ճաշ քաղաք» (“Name dish city”)? It’s fine if you haven’t, because you do now! What about h-pem’s audiobook of William Saroyan’s short stories? Or the radio-theater of Yervant Odian and Hagop Baronian humor pieces on YouTube by Yeghia Akgun?

Old short films such as Ara Madzounian’s award-winning “The Pink Elephant”, Tony Partamian’s Sunderland-awardee “Hrametsek,” and Vatche Boulghourjian’s Cannes-awardee “Fifth Column” have resurfaced and are being celebrated by a younger generation; Hamazkayin Lebanon’s Kaspar Ipegian Theater Troupe has started uploading its taped theatrical performances on YouTube.

It doesn’t end there, and it only gets weirder! Sebu Simonian giving us a virtual tour of the Dino Hall at the Natural History Museum of LA County in Western Armenian? Yes, please! A bolsahye telling me how to bake my Easter cheureg on his YouTube channel? Of course! Vahe Berberian and his weekly virtual talk show (which I always manage to tune into)? Also available!

I’ve covered artsy and audiovisual, but we’re still only halfway through. Western Armenian haikus are a thing now, thanks to Garin Bedian, who’s also part of a new community on Twitter, sworn to tweet only in Western Armenian, no matter the topic. As an excited member of this community, I texted my long-time friend Sevan Gharibian and new friend Sarin Akbas to found the first and only Western Armenian Telegram channel, «Ի՞նչ Կայ Չկայ», which already has an approximate 300 subscribers and serves to send custom-made fun-to-use stickers, tiny quizzes, literary pieces, and creative works. Not too far back, Hamazkayin’s “Kantsaran” launched a #ՏունըՄնանքՈւՍտեղծագործենք (Let’s stay home and create) online contest to encourage young Armenians to write poetry about the pandemic. The new Gulbenkian “Be Heard” Prize has sparked additional dialogue on how, and why, to discuss non-Armenian topics in Armenian and the importance of it all, pushing my community and above to create in a language that is too-familiar but only used to discuss the same few limited topics in an everlasting loop.

The education sector is also digitally thriving. We have so much online Western Armenian educational and pedagogical content, and unfortunately, for most of us in the diaspora, it took a pandemic to make the move. Alik Arzoumanian from Watertown, Mass., narrated a Dr. Seuss classic for her KG students which soon became a “YouTube sensation” and opened a whole new world for teachers in the diaspora to make the much-needed virtual move. From elementary math to anything and everything, these creators were extra encouraged by initiatives like Gulbenkian’s “Prizes for Teaching in Armenian Online”.

But kids got way more than they bargained for because it doesn’t stop at school-related learning! From Hamazkayin Canada’s children’s storytime Facebook live sessions, to Parev Arev’s now frequently-uploaded quirky rhymes; animated classic fairy tales by Pokrig; Lala and Ara encouraging kids to create and posting them for everyone to see; AGBU starting a free-of-charge Learning Zone initiative on their Armenian Virtual College; quality-dubbed Treasure Island; TUMO’s recent comic; my friend Sarin’s independent YouTube grammar classes; even storytelling in the Hamshen dialect; the list goes on… Soon, Nayiri.com will release a smartphone autocorrect and a group of international youngsters will publish fictional novels. I’m confident I missed out on so many more online content I might’ve come across. A few valid concerns brought to my attention by friends are worth noting, though. My friend Kourken Papazian pointed out how all this is “still a drop in the ocean of needed reforms”, and Kayane Madzounian was worried about how the abstract online presence of content would be treated once lockdown measures were lifted and physical presence of such content is nonexistent.

All this and we’re only halfway through 2020, and apparently, depending on whom you ask, only in the first wave of the pandemic. Maybe all we needed was a break from our daily non-Armenian lives to talk about our non-Armenian lives, in Armenian.

Maybe UNESCO was wrong all along and we’re simply too lazy to keep the language alive, and that’s on us.

Maybe we skipped the phase of making our language “cool”, “hip”, and “slangy” because we were too pre-occupied by post-genocide displacement, mourning, and immigration.

Maybe most of our curricula gears are stuck with everything that has to do with the traditional, leaving out all that interests kids and youth today.

Maybe we corrected and disputed the spelling and grammar more than we should’ve and drove our youth into avoidance altogether because, frankly, we don’t care if արեւ (arev | sun) is written with an է or an ե if we’re not publishing a book anytime soon.

Maybe we didn’t modernize the language enough, “taboo” vocab is close to nonexistent, our word for “sexy” isn’t sexy enough, and maybe because sexiness isn’t for Armenians.

Maybe it’s time the older generation considers giving us some space to breathe and create in a language that feels like home but also, somehow, too distant to be used in everyday life. This is your cue to stop telling me whether I can or cannot use կոր (“gor”), because I won’t, slang language is also language.

Maybe we’re on the right track, and maybe we’re too hesitant to use the wrong words, verbs, spelling, or grammar, but enough. My generation is often credited for impressing the older ones when given the appropriate time, space, and resources. So, give us exactly that, the benefit of the doubt, and we might prove UNESCO wrong.